The 2019–2020 fire season in Australia’s New South Wales saw an extraordinarily large number of bushfires damage or destroy a record land area and number of structures. This highlighted several areas that warranted improvement in terms of safety and efficiency, as RFS Assistant Commissioner Ben Millington discussed.

Background

The New South Wales Rural Fire Service (RFS) is the world’s largest volunteer fire fighting organisation, with around 73,000 volunteers, alongside more than 1,100 salaried staff. It fields around 2,000 brigades and 4,000 appliances over its 44 districts and it operates the State Air-Desk (SAD) for aviation coordination, not only for firefighting but as a whole-of-government approach for aviation response, with the exception of Police and Ambulance services. Assistant Commissioner Ben Millington is the RFS’ Director of State Operations and a key figure in the management of RFS aviation response. He elaborated, “For example, apart from firefighting, the State Air Desk coordinates aviation responses for the Department of Primary Industries for bio-security incidents, for Corrective Services to get tactical units to jails for public order incidents, or the NSW State Emergency Service when flooding impact various parts of the State.”

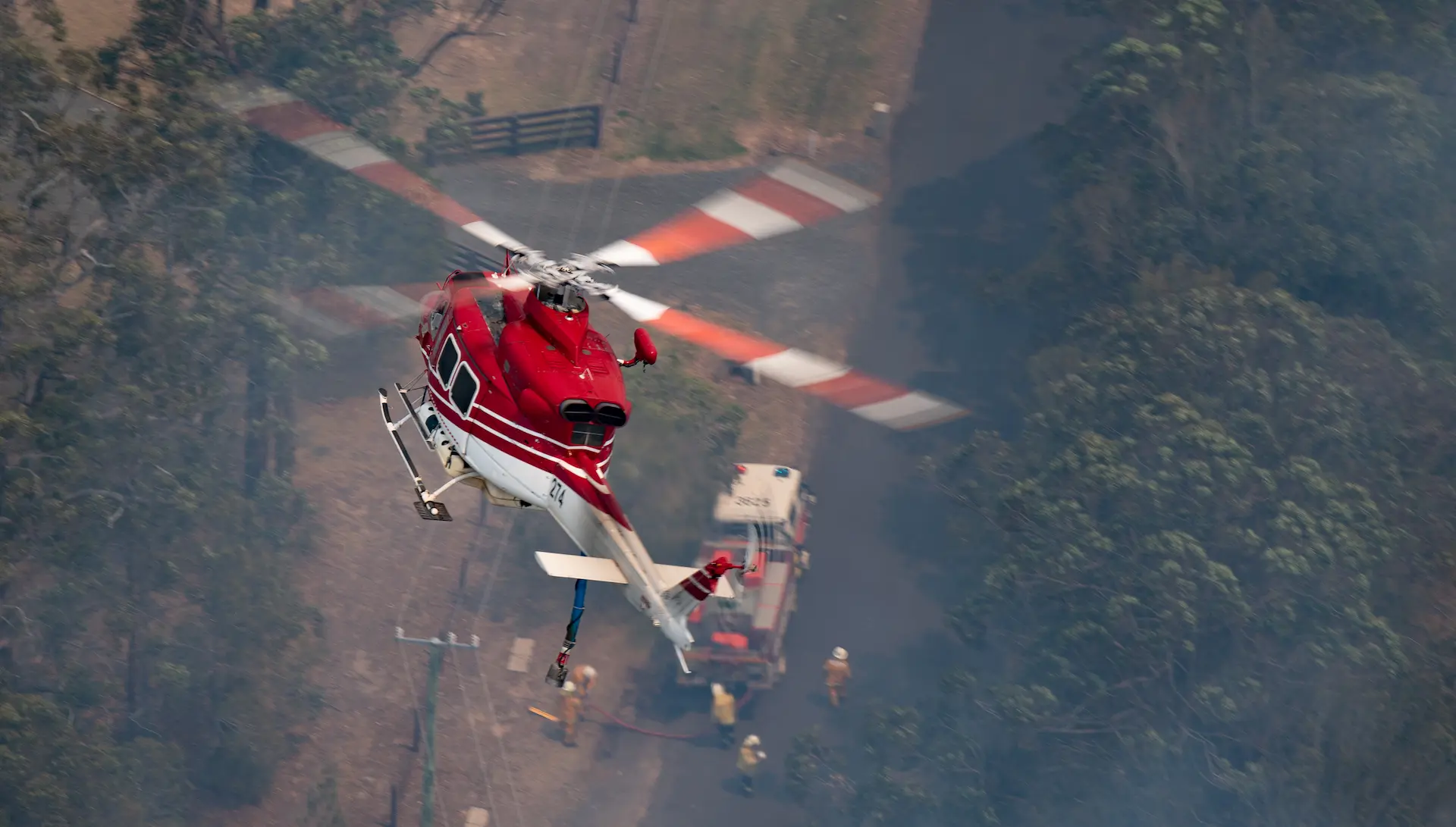

Millington explained that the RFS utilises three methods of obtaining aircraft to fulfil its function. The service operates its own fleet of aircraft, maintains a call-when-needed (CWN) arrangement with operators of almost 200 aircraft and enters contracts for exclusive use of about 40 additional aircraft during the fire season. The RFS’ own fleet includes a Boeing 737 Fireliner LAT (large airtanker), several Bell 412 helicopters that operate as SAR and aerial intelligence platforms or as bucketed firefighting platforms in remote areas, two BK117s for remote area insertion or SAR, one heavy type-1 Chinook helicopter and two Cessna Citations that operate as lead planes, personnel transport, or aerial intelligence platforms. “We use a lot of operators to support for firefighting operations in the State. We do have a very positive relationship with the aviation industry, and we rely on them very heavily but as we all know, challenges are increasingly presenting themselves in regard to aircraft availability,” he commented.

‘That’ Season

The 2019-2020 fire season was unusually protracted and high tempo with Millington reporting that it commenced in July 2019 and did not finish until March 2020. He said that more than 11,700 grass and bushfires occurred in NSW during the season, burning 5.5 million hectares across the State – around seven percent of the state’s entire land mass – and destroying more than 2,400 homes. Several factors contributed to the intensity of the fire season: predominantly an extended period (as far back as November 2016) of above average temperatures and minimal rainfall. 2019 was the hottest and the driest year on record for Australia and 98 percent of NSW was affected by drought prior to the start of the season. That proportion rose to 100 percent by January 2020 and those conditions led to an unprecedented size, scale and concurrency of fires, with spotting at much greater amounts and distances.

Aviation played a significant role in how those fires were combated and Millington stated, “We engaged 317 aircraft for firefighting purposes during that period and the highest number of aircraft on one single day was 160 actively tasked aircraft, flying and supporting us across NSW on 22 December 2019.” In total for the season, aircraft performed over 2,500 taskings and flew a total of more than 63,000 hours. The introduction of bush fire SAR (search and rescue) as a new concept for the season utilised RFS and Defense aircraft to search ahead of fires, getting information to those who may not be aware of the situation, looking for those in need of immediate rescue and getting them out of harm’s way. “That operating concept enabled us to successfully rescue 51 people,” Millington reported. Two VLATs (very large airtankers) and four LATs dropped more than 24 million litres of retardant or suppressant over the course of more than 1,700 missions but tragically, the season also saw the fatal crash of a C130 LAT on 23 January 2020 that resulted in the tragic death of all three US aircrew.

Inquiry

As is usual after any significant emergency incident, there was an independent State Bushfire Inquiry after the fire season ended and its report included a chapter dedicated to aerial firefighting and aviation operations. “The report acknowledged that aviation played a crucial role during that particular season,” noted Millington. “It addressed issues in regard to the demand for larger firefighting aircraft, recognizing that the demand is worldwide and impacts on how we can access and engage those services here in Australia. It also looked at the mix of aircraft that we engage here in Australia and talks about other issues such as aerial firefighting at night.” The report contained 76 recommendations and the majority of those were attributed to the RFS for it to action.

The ATSB (Australian Transportation Safety Bureau) contributed to a National Royal Commission into natural disaster arrangements in Australia, and its comprehensive research produced some interesting statistics. It highlighted the significant increase in aerial firefighting activity over recent years. It also found that around three quarters of recorded aviation incidents during the 2019-2020 fire season involved Australian-registered aircraft, but around two thirds of the more serious incidents and accidents involved foreign-registered aircraft.

The RFS also cooperated closely with the ATSB during its ensuing investigation into the Coulson C130 airtanker crash (January 2020) and the final ATSB report was released in August 2022, attributing three safety factors to the RFS, as Millington outlined. “It looked at our large airtanker tasking policies and procedures and our aerial supervision requirements, it examined our task rejection policies and procedures and it also considered at some of our initial attack qualifications and certification processes here in Australia,” he summarized. Although the Australians have minimum requirements for initial attack pilots and recognize the US Forest Service initial attack certification, the ATSB justifiably recommended a more rigorous approach as to how that is implemented and monitored in NSW.

ATSB View

Specifically, the ATSB report noted that the RFS is not an aviation organization and is not directly responsible for flight safety. However, it contended that the agency is closely involved in aerial operations, responsible for task objectives and selection of aircraft type for particular tasks, and the report asserted that the RFS therefore needed to play a greater role in managing those risk processes. CASA (Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Authority) recently conducted a surveillance campaign and worked proactively within the aerial firefighting sector. This resulted in a number of issues being raised, many by aviation operators and they include the lack of nationally standardized operating procedures, the fear of service allocation being detrimentally affected by the reporting of safety incidents and occurrences, inconsistent training standards, the absence of NOTAMs and fire information, and the lack of information and briefings to pilots. “That work is still being undertaken but a recent CASA-hosted workshop in Brisbane is certainly a major step forward in dealing with some of those issues,” Millington opined.

In addition to the State Bushfire Inquiry, the Royal Commission, the ATSB report and CASA’s surveillance, a coronial inquest is underway. Its report is due out soon. “We expect those findings to contain further recommendations for aviation and aerial firefighting,” Millington said. The RFS accepted the ATSB recommendations and is already actioning or has undertaken to action those matters. On the back of all the aforementioned inquiries and reports, the RFS initiated a comprehensive aviation safety project to address the issues raised. Although Millington accepts that there is a great deal of work yet to be done to address all the issues raised, a number of initiatives have already been implemented by the RFS. He advised, “We’ve developed and released an aviation dispatch/tasking rejection policy and procedure that provides some certainty and clarity when a pilot does reject a tasking. It initiates a number of processes whereby we can review those circumstances and ensure that other pilots on that fire are aware of that rejection, so they can factor it into their own decision-making.”

Initiatives

A number of doctrine policies and procedures have been updated, a dedicated LAT coordinator position has been implemented on the SAD for situations when two or more LATs are active, and the recruitment of a dedicated Aviation Safety Officer is well underway. Increased mental health for all personnel was raised as an issue and the RFS has subsequently engaged the services of nine psychologists to address this, in addition to its existing employee assistance program. Millington and several RFS personnel undertook a study tour to the USA, working with CAL FIRE and the US Forest Service to see if and how various aspects of their operations can be factored into the RFS model.

“There is lots of work still in progress,” acknowledged Millington. “We’re making sure our aviation operational structure is contemporary and fit for purpose, as well as looking to establish full-time Air Attack Supervisors and appoint dedicated Airbase managers. There will still be a role for our volunteers who are qualified and well-versed in those positions but the demands of a protracted season, day-in and day-out and the potential uncertainty of volunteer availability mean that there is a need for full-time personnel, just as we now do with our RFS aviation rescue crew members. We’re also committed to increase and improve training, particularly in regard to aviation operations.” A major step forward in training is the recent opening of the Aviation Centre of Excellence at Dubbo, which houses four aviation training simulators for fixed-wings and helicopters, two dedicated training spaces and extensive accommodation.

Technology

One ATSB recommendation was that RFS develops an electronic flight risk assessment and geo-spatial risk visualizer to assist in identifying where air operations are high-risk, based on a number of factors. As a result of that recommendation and as part of the drive to investigate and adopt new technologies, the RFS is continuing work on its world-first ‘Athena’ artificial intelligence-powered bushfire intelligence system, providing dramatically enhanced risk visualization, safety and tasking efficiency. (see related article ‘Goddess of Strategy, Ed.) “This technology will certainly assist us to get information out to pilots, safety alerts, advice around task rejection decisions and ultimately make it safer for everyone involved,” Millington stressed. The RFS operates a pair of Cessna Citations fitted with an overwatch system for aerial intelligence gathering that allows fire-scanning and that has recently been used to also support fire operations across the State, something Millington describes as a ‘major win’ for the RFS’ aerial intelligence gathering capability.

The service is investigating the deployment of ADS-B (automatic dependent surveillance broadcast) technology in aerial firefighting aircraft to enhance situational awareness and airspace management practices and it is holding ongoing discussions to develop consistent aviation doctrines across jurisdictions to increase understanding and interoperability. “There is clearly a need for national doctrine, and I see that as the biggest step we can take to increase consistency and safety throughout the Australian industry and firefighting sector,” Millington remarked. For its part, CASA is looking to strengthen fire-traffic exclusion zones above firegrounds to minimise civilian traffic interference with fire operations.

In closing, Millington stated, “Aviation safety must and will always remain a high priority for us and we in the aerial firefighting industry need to work together because no single agency, operator or government department can do this alone. Everyone is talking more and more about collaboration to increase consistency and interoperability. If the fifty states of the continental US can achieve such high levels of standardization for that purpose, there is no reason that we can’t adopt a similar approach here in Australia. It requires input from all stakeholders, not just firefighting agencies.”

HOME

HOME