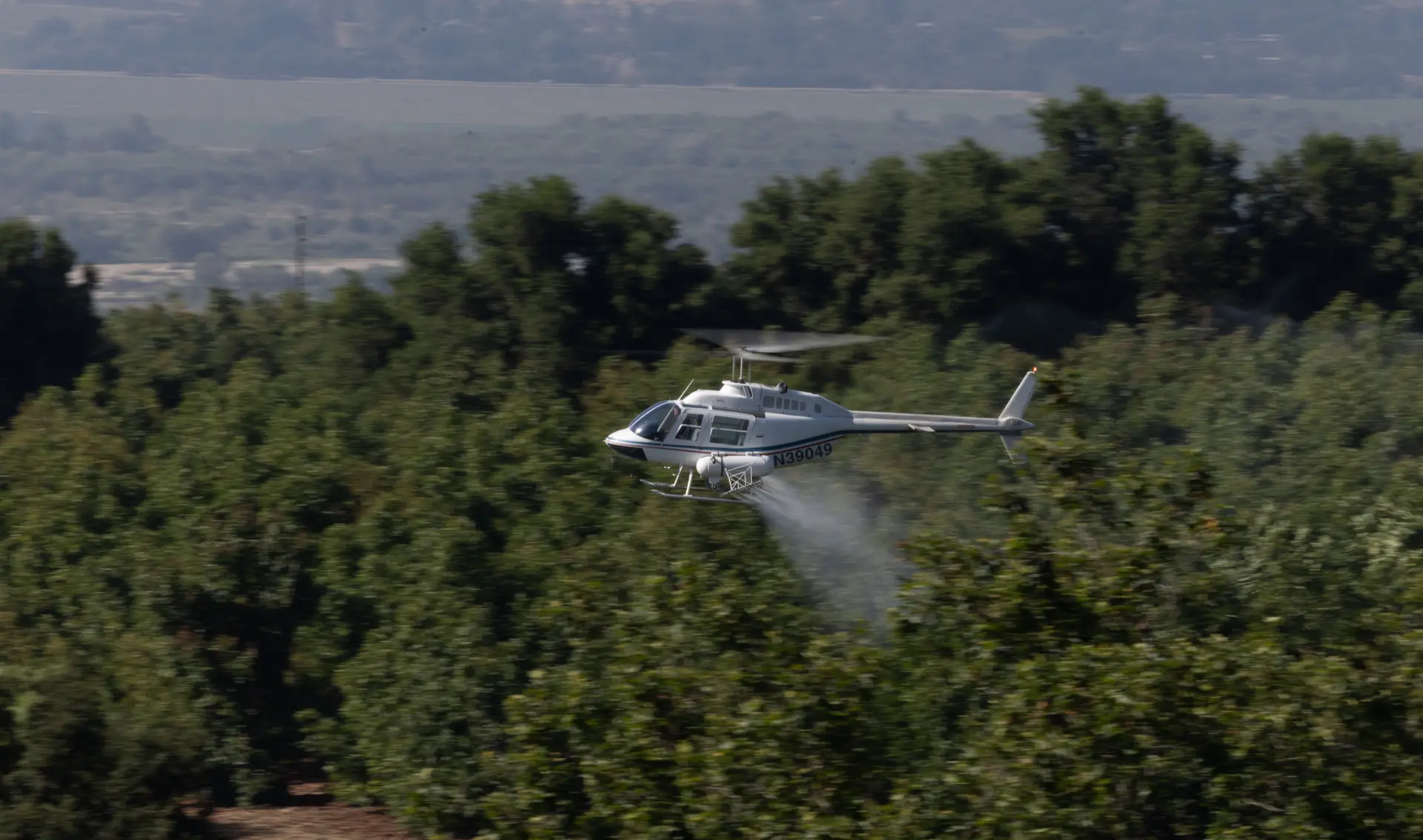

Aspen Helicopters in Oxnard, California, operates various types on a wide range of missions. A mainstay of their operation is agricultural work with Bell 206 series aircraft, which accounts for maybe one-third of the company’s business.

Rob Scherzinger runs the ag’ division for Aspen Helicopters and has been ag’ flying for over 50 years, gaining his first crop-dusting experience back in 1979. Rob, along with two partners, co-founded Aspen Ag Helicopters in 1985. The company’s ag’ fleet includes three Bell 206Bs, all running Isolair spray equipment that has been optimized so that the rotor vortices are used to curl the spray swathe up to hit the underside and bottom of the trees and Scherzinger commented that he considers the JetRangers to be the perfect tool for the job. The division employs three ag’ pilots along with Scherzinger, who now flies much less than he used to. “Our three pilots do a good job,” he noted. The ground crew comprises seven drivers, mainly long-term employees, with one boasting 23 years at Aspen.

According to Scherzinger, the choice of the JetRangers for agricultural work was initially made so that they could be used for dual roles of both ag’ and charter work, although in recent times, the charter work has been taken over by newer and more appropriate types. “We have a really good maintenance department, and we don’t have any parts issues other than a current hold-up with rotor blades,” he stated. He added that the 206s have fairly similar operating and production costs to the Bell 47 and although sourcing spare parts is starting to become more difficult, it is not nearly as problematic as it is for the older, smaller 47 series. The three Aspen 206s are all 1980s vintage with around 20,000hrs but are maintained to a very high standard.

Application is typically carried out at between 20 and 24kts, varying slightly depending on the volume per acre required. The sprayed product can be a combination of materials that fulfils more than one function. For example, a spray oil is used to spread the pesticide, and it also acts as a suffocate on the mites, while foliar nutrients are regularly added to the mix. “They’ll hit the leaves with phos’ acid, or maybe some potassium nitrate or other minor elements,” Scherzinger explained. He noted that trees do not like oil, so the volumes are sufficiently low that the trees are not distressed, but the application is heavy enough to be effective against the mites. Flying in summer typically commences at around 6:15am. It continues until either work is completed or the temperature reaches 86oF (30oC) – usually between 1pm and 3pm – when spraying is halted as per the product label to prevent leaf burning.

The ag’ work is a seven-day operation, primarily throughout the Los Angeles, Ventura and Santa Barbara counties, although the company is

registered to operate in six or seven counties. Scherzinger commented that they even flew on July 4th, and although that generated several

complaints, he pointed out that spraying is a necessary function. Some growers who didn’t keep up with the spraying lost up to 30% of their

crops last year. All crop spraying is with pesticides or fungicides and the company does no herbicide spraying other than on the faces of

dams.

California is one of the world’s primary produce-growing areas, and typical crops include avocado, lemon, strawberry, celery, Brussel sprouts and artichokes. “Celery is probably our biggest row crop, but we don’t usually do a lot of row crops unless it rains heavily and the tractors can’t get onto the fields to spray,” Scherzinger advised. Spraying is a year-round mission in California although some times of year are much busier than others. Lemons are sprayed all year, avocado crops usually require aerial attention from May to July or August, and most row crops are sprayed during the winter. Scherzinger remarked that the timing of spraying can be critical, with the most effective product used to control thrips on avocado trees having a fourteen-day-before-harvesting minimum delay. Other products are available with shorter times to harvest but are not as effective, so they are only used when urgent circumstances closer to harvest necessitate it. Typically used products on produce other than avocado have a time-to-harvest of only one to three days and are much less toxic than the broad-spectrum products used decades ago but control a much narrower range of pests, so a greater range of products is necessary to fulfil all required control operations.

Aspen also has contracts with California State Water Resources and Los Angeles Metropolitan Water, spraying copper sulphate on the drinking water reservoirs to kill algae. “Depending on the time of year and the climate conditions, you get a build up of certain types of algae, and it’s interesting that some types of algae grow up from the bottom, some float on the surface, and some in between. The size of the copper sulphate pellets determines what depth it’s effective at so we have to tailor the pellet size to the type of algae being targeted,” he explained. “We also do a lot of greenhouses, spraying the roofs with paint when it’s really hot to adjust the temperature and UV light, so that’s raspberries, cucumbers and tomatoes and when it cools down, we’ll often spray the roofs with solvent to remove the paint.

California is not the easiest state in which to operate agricultural aviation, and Scherzinger commented that the compliance workload and

costs have become almost overwhelming. The Department of Agriculture for each county has inspectors that can come out and do a field

inspection at any time. Scherzinger explained, “They’ll come out and want to see the work order, see that you’ve got all your safety gear

on, there’s 20 gallons of fresh water for each person and that we’re not doing anything we shouldn’t be. Then, after every day’s work, we

complete a pesticide use report, specifying what we sprayed and exactly where, and the state compiles all that on a massive computer in

Sacramento.” Fog is a frequent issue, and Scherzinger stressed that he constantly reminds the pilots to always leave themselves a way out,

to remember suitable landing spots on the way into a job and commented that climbing up through the cloud was only an option in an extreme

emergency.

When the pilots finish one day’s work, they must plan for the next day and beyond. Every registered beekeeper is recorded on a website, and those within a mile of the intended spray area must be identified and notified of the operation at least 48 hours in advance. “That’s for every job we do, and it'll typically be ten or fifteen beekeepers each time,” he added. “We also have a list of people that we’ll call for certain jobs because we’ve been here a long time, and virtually all our customers are repeat clients, so we know who has sensitive neighbors, who has horses and things like that.” Most loading sites have also been long established, clear of stock and horses and dusty areas, and loading is carried out on the ground rather than from a truck-mounted deck. Scherzinger explained that he considered the ground option to be safer and noted that in his 45 years of ag’ flying he had seen everybody take off at least once with the fuel hose still attached.

One particular senator even put forward a bill – yet to be passed – to require DMV (Department of Motor Vehicles) registration of general aviation aircraft as he believes they are not paying their fair share of the costs of air pollution. Scherzinger responded by spending three days making a spreadsheet that recorded all permits, taxes and licenses required for Aspen Helicopters to stay in business. “That was three pages long and came to several hundred thousand dollars that we are already paying to the state and federal governments every year,” he reported. Unsurprisingly, he got no response when he sent it to the senator, and he wonders why it is being made so difficult to stay in business, especially when the state economy is so reliant on agriculture.

One Aspen ag’ pilot is in his mid-sixties, and Scherzinger commented that he would be looking for a new ag’ pilot in the foreseeable future. The position may not be easy to fill as ag’ flying is very different from almost all other operation types. It is ingrained in pilots that altitude equals safety, and the more clearance above terrain and obstacles there is, the better. Spraying is optimally carried out at just six or seven feet above the crop, obstacles permitting, so it takes a particular type of pilot to be comfortable and competent in that higher-risk, minimal-margin environment. “We’re in the dead man’s curve at max’ gross weight all day with around a hundred takeoffs, and it’s such a different type of flying that it goes against everything we’ve learned,” Scherzinger observed. Nevertheless, Scherzinger still enjoys his job and the industry, and when the right person comes along to fill the next vacant pilot position, they will be equally enthusiastic about working in the demanding, taxing, but immensely satisfying environment that is ag’ flying in California.

HOME

HOME