Powerline flying presents challenges and hazards that differ very little, no matter where in the world it is conducted. Procedures, methods, and policies to effectively cope with those risks, however, can vary between different counties or locales. HeliOps’ Ned Dawson spoke to experienced utility pilot Ned Lee about powerline flying in New Zealand.

Network Maintenance

New Zealand’s national power grid – the high-voltage electricity transmission network – is owned and managed by Transpower, a government-owned enterprise that does not generate or sell electricity but provides the infrastructure and market systems connecting electricity generators to major users and distribution networks. Transpower’s 2022 contracts were awarded to six service providers for the network’s maintenance needs and these companies contract with helicopter operators for aerial support when necessary. One such operator is Advanced Flight, an Auckland-based business that was established in 1998, originally as a helicopter charter and management company.

Ned Lee is Advanced Flight’s full-time chief pilot, and he joined the company in 2015. Lee has been conducting HEC (human external cargo) powerline work since about 2011 in New Zealand, Canada, Alaska and China, and his wealth of utility work experience enabled the company to branch out into varied aerial work operations. “I project manage all the utility work, which includes all the powerline flying, firefighting and external load work,” he outlined. With Lee on board and an ex-VIP Bell 429 available for the company to lease, Advanced Flight immediately looked at introducing the Bell twin to powerline work and subsequently became the first operator in the world to use the type in that role.

The first powerline job for the B429 was a line-testing project, utilizing a lineman that Lee has worked with extensively. “That made it pretty easy as the team gelled straight away,” he remarked. The new type requires little additional training for the linemen, who already receive significant instruction before qualifying for any helicopter operation with Advanced Flight. “In the past, a new lineman would get a fifteen- or twenty-minute briefing at the start of the day and then we’d hook him onto the rope,” said Lee. “A lineman who’s not performing on the line will make even the best pilot look really average and I soon learned that spending a full day educating linemen on the ground was the key to increased safety, efficiency and productivity.”

Linemen are now trained in the classroom with videos and other educational material that covers the full gamut of their role, including CRM and effective communication, and Lee noted that his experience in other countries had provided valuable insight into effective training methods. “I spend a whole day with them and show them videos from my perspective, looking out of the helicopter, and showing them good and bad examples of how to operate on the line.” The comprehensive training gives the linemen a good understanding of the mental workload on the pilot and the limitations of short-term memory, so when flying, they act as extra eyes for the pilot, constantly reporting any hazards around the aircraft and then regularly re-stating the hazard until it is no longer relevant. “Obviously you build a relationship with linemen you work with regularly and that makes the work go a bit easier, but you often get new linemen to train up, or new clients that you have to build a relationship with and train.”

Inconsistent Demand

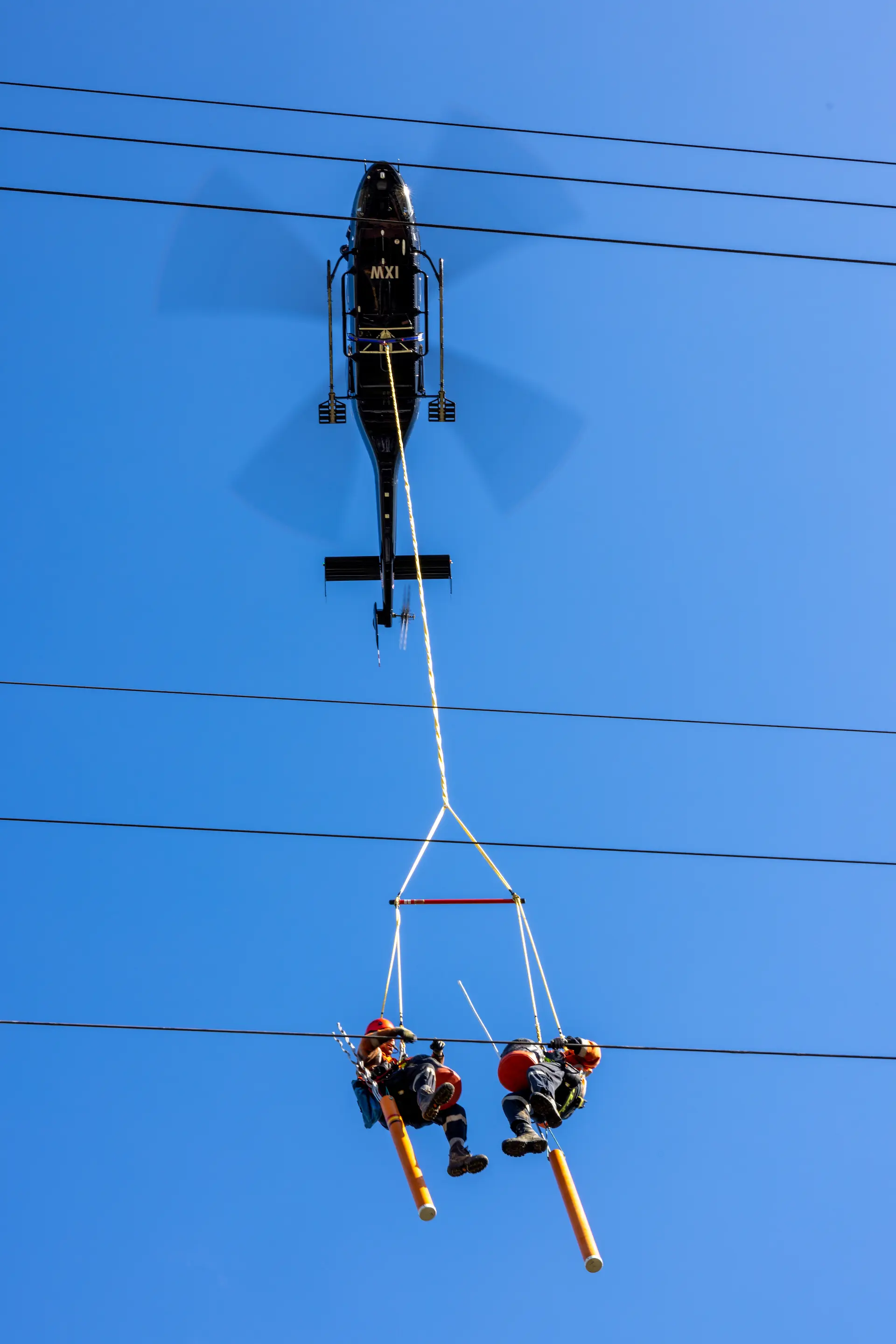

Due to the limited scale of the New Zealand network, powerline flying is not a full-time task for aerial support operators, and it is normally carried out as contract work for the various service providers that contract to Transpower. The availability of work is rather inconsistent, and Lee commented that a project might run for a few days or even four weeks on end, but then no work might come up for six months. He cited that inconsistent demand as part of the reason that he began chasing powerline work overseas, in order to maintain a high level of proficiency. “Our powerline work is mainly for maintaining and testing the lines, so we do human sling work, but there’s only a limited amount of this specialized work,” explained Lee. He went on to describe the particular challenges of longline sling work on HEC operations. “There’s very limited visual reference, and different span heights or surfaces can make it even more challenging. The higher it gets, the harder it gets and spans on a hill, for example, make it more difficult, while the closer the span is to the ground and the more surface variations such as bush and fences, the easier it is.” He also acknowledged that a good lineman who is steady and stable on the line makes the job easier for the pilot, as a lot of the visual reference is related to the lineman’s body position.

As the power grid covers the whole country, the work environment varies from all types of rural and wilderness terrain to towns and cities. This variety of environments creates an equally diverse range of challenges for the powerline pilot, as Lee recounted. “In remote areas you might have big valleys with very little reference or be dealing with stock issues. Powerlines run through farms, and you don’t want to chase horses, cows, or deer through fences because they get frightened by the helicopter. Then, in the cities you’ve got compliance with all the civil aviation regulations for managing risk when operating over houses and roads.” An inner-city job that Lee flew during HeliOps’ visit was for maintenance contactor Northpower, over Auckland city and within the control zone, which entailed managing separation from arriving and departing airline traffic, as well as using a ground crew to prevent public access into the work area below the helicopter. A normal day commences with transit to a staging area, where a thorough ‘tailgate’ briefing is carried out with all personnel. “After that we get straight into it. We’ll stop for a bit of lunch but if we can, we’ll just keep at it until the job’s done,” Lee advised, and explained that while rural work usually permits quick moves from site to site and a steady, productive workflow, work in urban environments usually entails frequent and regular stops for the helicopter crews as they wait for ground crews to secure traffic management and the area under the helicopter’s workspace.

Crewing

The normal crew for Advanced Flights powerline work includes the pilot and an additional crewmember in the aircraft cabin, who acts as the pilot’s second pair of eyes for situational awareness and monitors the aircraft systems while a lineman is on the line. “As the pilot, your focus is the guy on the end of the line,” Lee explained. “If he takes ten minutes to do a repair, you can’t put your head back in the door for that entire ten minutes - because you have to hold him accurately in position - so the extra crewman is trained to watch the aircraft gauges, power settings, fuel and so on. He also monitors the rotor wash and watches for things like stock or traffic.” The extra crewman is usually also a pilot, and, in an emergency, they will release the bellyband on the pilot’s command and help with cockpit procedure, engine calls and so forth.

Unlike some other countries, New Zealand does not allow platform work on powerlines, deeming it too high-risk, so all line maintenance and testing work is underslung. “Visual reference may be a little easier on platform work, when you’re right next to the wire,” opined Lee, “but it’s a lot more comforting when you’ve got the lineman on a 100ft line and you’re that high above the wires. If there’s a gust of wind or something goes wrong the helicopter can move around all over the sky and you’re not going to hit a wire.” The usual line-length in New Zealand is 100ft but Lee has used lines varying from 75ft to 180ft on powerline work, and even a 220ft line on one occasion when inspecting a mast’s guywires. The length of line can be dictated by the distance between the phase wires, and he remarked that he used the 180ft line on extremely tall towers in China with widely spaced, very high-voltage phases, but that it was surprisingly easy to work with as the wires were so thick that visual reference was easier than on the thinner wires used for the lower voltage lines in New Zealand.

Safety in HEC

Redundancy is a necessity to ensure safety in HEC operations and Advanced Flight’s 429 carries the underslung linemen with two points of attachment. The primary attachment is to the aircraft’s cargo hook and a CAA-certified bellyband that passes through the cabin provides the redundant second point of attachment, both attached to the two separate dielectric (non-conductive) lines – a primary and secondary – connected to the linemen’s harnesses. The same equipment is used for work on either energized or de-energized lines and at least half of Advanced Flights powerline work is on energized lines, so the dielectric lines are an absolute necessity, as it is common to be touching two or three live phases. The lines are tested daily to ensure they retain their non-conductive property and if a cargo-hook failure results in shock-loading of the bellyband, that band is immediately deemed unserviceable and retired from use.

Lee explained that the principal reason for choosing the B429 was a requirement that helicopters on powerline HEC work in New Zealand be twin-engined and capable of hovering OGE (out of ground effect) on one engine. “In days gone by, we could use aircraft that weren’t able to hover OGE on one engine, so we could use twin-Squirrels and the older BK117s, that type of thing, including at one time using an AS350” Lee related. In 2010, New Zealand company Airwork developed the BK117-D2, installing more powerful LTS101-850B-2 engines and Lee described that type as the initial leader in the power industry. “You want a helicopter that’s not too big, but powerful enough to hover on one engine OGE, with a couple of linemen on board and two or three people in the aircraft and the 429’s performance on one engine is on a par with the D2,” he stated. “The BK is basically the old Toyota Hilux of the industry. They’re an incredibly tough and reliable helicopter, but with the 429 we’re getting into much more modern technology so dealing with an engine failure – if you ever had one – would be a heck of a lot easier with the FADEC engine controls. The caution warning system’s more advanced and the crashworthiness is much better too.”

An advanced communication system is used, connecting the linemen to the aircraft intercom and permitting multiple inputs without cutting each other out. Lee explained that this was a major safety benefit, as with the more common VHF FM voice-activated radios, more than one person trying to talk at the same time results in blocked transmissions. “This system is excellent because as part of the intercom you can talk over each other, and the person with the most urgent thing to say can just get louder and make himself heard. The linemen can also hear our incoming radio calls, so if their information isn’t too important, they can wait until the radio’s quiet before passing it on.”

Lee has flown BKs, twin-Squirrels, the B3 Squirrel and B429s on powerline work and cites the 429’s superior power margin, lower mental workload for the pilot and higher safety levels as its greatest advantages in the role. “If you can minimize the cognitive workload through good cockpit ergonomics and systems, that increases your capacity to process situational awareness, which is a key factor in safe operations in the powerline environment,” he elaborated. Lee commented that Advanced Flight’s ethos of doing everything well and exceeding expectations lets them achieve their desired high operational and safety standards. Transpower and the contracting service providers were receptive to the introduction of the Bell, but one minor challenge was the standard requirement for 100hrs on type. “Because it was the first of type, we argued that there was no way we could build 100hrs without putting it into this environment and I pointed out that I did have more than 1,000hrs operational experience in the powerline environment already,” recalled Lee. He reported that Transpower was reasonable about it and wanted to get the benefits of the safer modern technology, with the only potential sticking point being the higher cost of the newer type. “That can be hard for a customer to get their head around because it costs a bit more but on paper it does the same job as the BK and it’s really hard to quantify that extra safety margin.”

429 Proved

Despite any initial challenges or doubts about the new mission for the 429, the Bell twin has now well and truly proved itself to be a capable performer in the powerline role. Lee is complimentary about the type’s capabilities, ergonomics and effectiveness, but stated that he gets his greatest enjoyment from the people he gets to work with, and the challenge of working in such a demanding environment. “You have to do it properly because there’s a lot of risk to manage but that in itself is enjoyable. Plus, you’re working with good, capable people who are of a similar mindset and manage risk on a day-to-day basis. It’s very much a team effort and a good pilot can’t go out and do this job well unless he develops a solid relationship with a good lineman.”

HOME

HOME